Currently, we are in the heart of what feels like a largely unprecedented situation as our global community responds to the risk of the novel coronavirus and COVID-19. For many—if not most of us—this has led, to varying degrees, to a compromised sense of wellbeing, be that physically or psychologically.

While the physical consequences of the pandemic are quite evident, the psychological are more subtle and insidious. And if left unaddressed—or at the very least unrecognized—they also pose a serious threat to our already vulnerable sense of wellbeing.

In this article, I’ll address the risk that current events pose to mental health on a more general, societal level, the implications they can have in the professional arena, what can be done to mitigate the attendant risks, and what this experience can teach us about compassion and self-care.

The societal impact

In this landscape of tremendous uncertainty, it’s only human and natural to experience feelings of stress, anxiety, sadness, and fear. We may also be experiencing various degrees of grief and loss, mourning the sense of normalcy, predictability, and safety that we’ve been forced to leave behind.

For many, the primary source of these emotions is the novel coronavirus itself and the public health risk it presents. However, as we’ve already seen, it’s triggered a ripple effect of interrelated consequences that compound its severity.

Professionally, many people are now facing uncertainty in terms of stable employment and financial hardship. Food insecurity may become a more pressing need for individuals for whom this was not necessarily an earlier concern, and for those who were living with food or financial insecurity prior to this pandemic, this will only be amplified. This public health crisis will also, understandably, potentially bring about fears related to access to health insurance and healthcare as those needs arise.

Furthermore, as individuals and communities we are facing unparalleled barriers to our typical outlets for social connectedness. We are inherently social creatures, and derive such a primal sense of our wellness from our connectedness to others.

There are clear limitations to that now, and with guidelines in place for physical distancing to help prevent the spread of infection, we are needing to explore new ways in which to feel connected to those we care about, and who care about us. While we have technology to aid in this, the truth is there simply aren’t any comparable substitutions.

Conversely, those who are sheltering-in-place with even the most loving and supportive friends, family, or roommates, may very well be craving a sense of personal space, after sharing close quarters for extended periods of time.

Consequences in the workplace

Over the last month or so, those fortunate enough to do so have transitioned into working remotely. Lately, I have been speaking a lot with folks about this reconciliation that seems to now be taking place of the “romanticized” idea of what productivity could look like while sheltering in place or working from home.

When this first began, some may have had rather lofty expectations of what could be accomplished. However, when working from home—especially under these circumstances—there are several factors that can hamper productivity. Here are a few examples:

Virtual communication is an imperfect substitute for the real thing

With new professional workflows, especially those that rely heavily on virtual communication platforms like Slack or Zoom, screen fatigue can become a very real thing. Additionally, it can be really difficult at times to achieve the same depth of communication through these platforms that one could achieve face-to-face.

Often on video chats we have limited non-verbal communication to work with to give context to dialogue that is happening (posture, hand gestures are more difficult to discern, and even eye contact, which is so important when we are seeking to be seen and heard, is challenging with this technology.) A lot can be “lost in translation” here. This can impact not only our productivity, but can contribute to unintended miscommunications amongst coworkers.

Mixing personal and professional spheres can affect sleep

Another area of concern is the extent to which sleep and energy levels can be impacted during this public health crisis. While working from home and sheltering in place, there are a number of factors that can contribute to insomnia and fatigue.

Aside from simply the psychological stress of this pandemic, working, sleeping, and playing all in the same place is not conducive to great sleep hygiene (i.e. habits that are likely to contribute to restful and restorative sleep).

We typically rely on separation of…spaces to cue our nervous systems about where sleep and rest are to occur, as opposed to which spaces are meant for “productivity,” or physical or mental activity.

We typically rely on separation of these spaces to cue our nervous systems about where sleep and rest are to occur, as opposed to which spaces are meant for “productivity,” or physical or mental activity. Many right now may not have home offices to keep work and home tasks separated, so when these spaces overlap out of necessity, we may find that our minds and bodies have a hard time shifting back and forth between rest-oriented and work-oriented needs.

We may also have less exposure while sheltering at home for most of the day to full spectrum light, or certain forms of preferred exercise, which our nervous systems also rely on to activate during the day, and to combat feelings of fatigue. This is why it is really important to find creative and workable ways of moving our bodies that feel vitalizing to us during this time!

It’s much harder to compartmentalize roles and responsibilities

Furthermore, while sheltering in place, there is a novel role conversion that may be coming into play. Roles in which we may have previously operated in more compartmentalized fashions are now overlapping—parents, for example, are potentially serving as parent/professional/teacher simultaneously.

Also, we may be taking on new caregiver roles that were not previously needed, thinking about what we can do to protect those in our life who may be more vulnerable right now (for physical, economic, or psychological reasons) and possibly needing to do so from great physical distance.

It’s difficult to plan for the future right now

Lastly, because there is a lack of clarity, at this moment in time, regarding just how long this pandemic will be impacting our lives and our communities, globally, it is difficult for us each to “psychologically pace” and plan for the future.

Whether that is in the professional realm (companies recalibrating projects and goals) or the personal, where those in the workforce may also be coping with disruptions in non-work-related domains of meaning. For example, family celebrations, weddings, birthdays, even planning for routine, “non-urgent” medical care.

In general, prolonged stressors such as these stretch our psychological bandwidth. Almost as though we are rubber bands being stretched, by sources of physical or mental depletion, we can feel less resilient to added stressors the more stretched we become. We can start to feel this physically, emotionally, spiritually, behaviorally, and interpersonally.

Why should employers be mindful of this?

This goes without saying, but those who run companies and those who work for companies are, of course, are all human beings. Fascinatingly, neither is immune to the demands and stressors this pandemic has brought to life.

Awareness of the above mentioned phenomena can lend itself, importantly, to an exercise of compassion for others (employees having compassion for their employers, employers of course having compassion for their employees) and reasonable expectation setting as we weather this storm together.

What can employers do to help guide their employees through uncertain times?

Stick to your values

In times of uncertainty it is helpful to anchor to values. There may be certain communal, company, and/or institutional values that are resonating with employers right now given these circumstances, and while some “core values” of a company may feel unchanged, they can also be dynamic, and evolve with shifting circumstances.

One way to help identify guiding values could be for employers to imagine…what themes would you want emerging from the story of how, as a professional community, you made your way through [this period of uncertainty].

One way to help identify guiding values could be for employers to imagine, at some point in the future, when we are hopefully safely on the “other side” of this pandemic, what themes would you want emerging from the story of how, as a professional community, you made your way through. And then ask, and check in with employees, what are the actionable things that can be done, right now, to move closer to that vision.

Communicate openly and honestly

Another potentially helpful step that employers can take right now is to encourage open conversations with their employees about expectation-setting during this time, knowing that more likely than not it will require flexibility, experimentation, and patience.

It may help to be mindful that, in the midst of this public health crisis it is not “business as usual,” so expectations may need to be re-calibrated, with a healthy dose of compassion, to account for the additional sources of depletion folks may be contending with.

Encourage ergonomic best practices

Regarding screen fatigue, if this is happening in specific workplaces, encouraging diversified methods of communication, and screen breaks, for employees might help.

Employers can also take the opportunity to encourage safe movement and connection for employees during this time. Modeling stretching breaks during calls and virtual meetings, and team check-ins on non-work-related needs might be welcomed. Check in with your employees and ask what their needs are during these unconventional times, and exercise a willingness to listen.

Be supportive of boundaries

Finally, it’s also important to remember that, while often thought of as something undesirable, a workday commute for many may have served an interesting function, providing a buffer of sorts between the work and non-work-related time of one’s day.

In the absence of this, employees may find themselves feeling more hurried. If employers are able to support employees in finding transitional time and boundaries at the start and end of the workday, that may prove restorative.

What steps can employees themselves take to safeguard their mental health right now?

I have been encouraging those with whom I am working to take regular inventory of their mental health and stress levels, as this can manifest, subtly or discernibly, in a number of domains:

Physically: muscle tension and aches—which, of course, are made worse by inactivity or less than optimally ergonomic home work environments—fatigue, or sleeplessness.

Emotionally: which may be observed as low mood, irritability, or nervousness

Cognitively: having difficulty concentrating, for example.

Behaviorally: eating more, or less, turning to substances in some cases as a form of self-soothing or escape.

Interpersonally or spiritually: for example, feelings of inadequacy, powerlessness, or feeling directionless.

The more aware and in touch we are with the temperature of our own stress levels, the more likely we are to be able to make proactive choices in terms of caring for ourselves.

In times of stress I think it is also helpful to identify where we can workably exercise a sense of control. There are also variables here we cannot directly control (i.e. the behavior of others, be that loved ones or community members who may be struggling to adhere to safeguarding guidelines, to the actions of those exercising decision-making in certain political realms). This is really difficult—honor that. Be gentle with yourself and others, and focus on what is actionable. Right now this could include:

Define a sustainable framework for media consumption

Too little knowledge, and we may not be armed with the most important information to properly safeguard our wellbeing, and too much (or the wrong kind—i.e. not grounded in proper evidence, overly editorialized or sensationalized) and we can become oversaturated, or feel paralyzed.

Seek out evidence-based and reliable sources of information, and try to set aside intentional times to check in with these so they may inform actionable choices on your part, without them dominating your day.

Disable notifications

Experiment with disabling instant notifications or news pop ups, or limit media exposure during times of day you might feel most vulnerable to feelings of overwhelm, or when you might be less able to translate that information into productive action. Perhaps pair this with some “strategic reflection time,” to journal, reflect, or give voice to what weighs heavily on your mind.

Stay connected

Stay connected to others, however you can. Double down on it, in fact. Check in on others and see how they are doing. When you connect with others, remember that you also are performing a public service. We can improve our sense of well-being from knowing we’re supporting others. It is also ok to talk about subjects outside of this public health crisis—it may be a welcome distraction!

Practice gratitude

Practice gratitude in ways that feel authentic to you. This means not making a gratitude practice obligatory to the extent that it feels forced or dishonest, but taking time to cherish the facets of appreciation that may emerge from this time of hardship. They are there, big or small, if we seek them out.

Practice mindfulness

Savor a practice of mindfulness. It is natural for our minds to ruminate on the unknowns of what the future might hold, or feelings of loss or pain that have transpired.

This is what minds do. Ground yourself in the present moment. Be a witness/observer of something you are experiencing moment by moment (in body, in thoughts/mind, emotion, spirit), without judgement. Breathe into “what is,” right now, whatever that may be.

Rely on your values

Lean in to your values—they help to give us a sense of purpose and meaning, and guide us through the fog of uncertainty. For some, this may be a value of service, community, humor, nurturance, curiosity/learning, citizenship/advocacy, creativity/creation, or transcendence (connecting with nature, those forces that were here before us, and will remain long after). Check in regularly with yourself to see if you are moving into/toward these values with your choices each day, or drifting away from them.

Be compassionate

Try to exercise self-compassion (treating self with the tenderness you might extend to others in your life). It is a relatively simple premise, but difficult to practice. Perhaps this could be around expectations of productivity; rest and self-care are important, and require discipline just as much as other projects.

Also exercise self-compassion for the anxious human mind. It is ever vigilant, scanning the horizon for potential harm that could befall us—it has evolved over countless generations to do just that. Step back and thank it for trying to protect you, even when this feels intrusive at times.

Use self-care to structure your day

Get back to basics; the foundations of self-care: physical movement, good nutrition, hydration, maintaining some semblance of a scaffolding or schedule to your day, and time for rest are critical.

Take slow, deep, intentional breaths (exhale for twice as long as your inhale)—this activates the part of our autonomic nervous system that can help bring us back to homeostasis after our “fight or flight response” is activated in response to stress. Try even inviting some collective deep breaths together with those in your world (kids, partners, and coworkers even).

Don’t be afraid to ask for help

Know when it is time to call for help; don’t go at it alone. Many mental health providers are offering care via telemedicine (secure video conferencing), and are there to listen, and offer guidance.

Additionally, there are a handful of public mental health resources, which I’ll list below, that will be of interest to those looking for additional positive coping mechanisms.

Public mental health resources

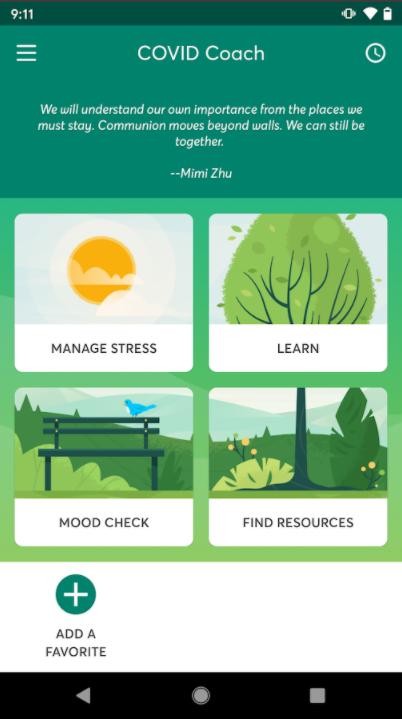

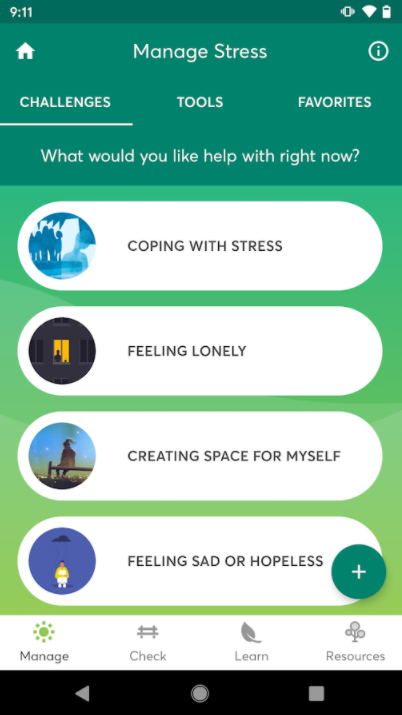

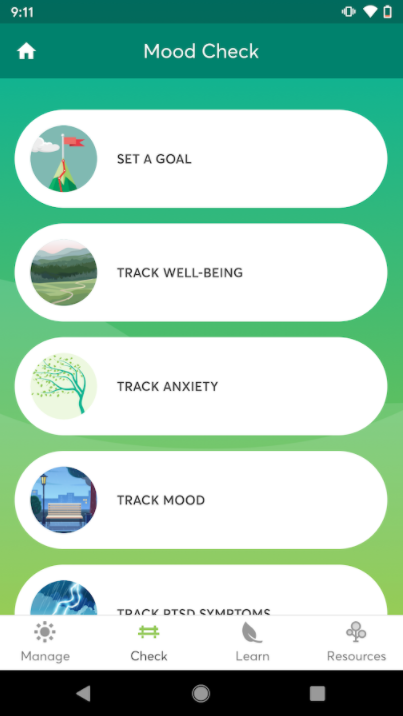

One relatively new resource I can recommend is a government-developed, free mobile app called COVID Coach.

As described by the app’s developers: “COVID Coach offers access to anxiety management tools such as audio-guided mindfulness and deep breathing, as well as exercises designed to address anxiety, trauma reactions, and relationship conflict. It also has quick links to resources for finding crisis care and mental health support, and service agencies for families and those seeking basic fundamentals. Developed by the National Center for PTSD at the VA, it joins other free, widely-used mental health apps like PTSD Coach and Mindfulness Coach.”

Additionally, here are some other resources my colleagues and I have compiled from reputable sources:

For stress and anxiety

- Managing Anxiety and Stress (CDC)

- Feeling Anxiety about Coronavirus? A Psychologist Offers Tips to Stay Clearheaded (UCSF)

- 10 Tips to Settle Coronavirus Anxiety (Mindful Living Counseling Services)

- Coping with coronavirus anxiety (Harvard Medical School)

- Feeling Anxious about COVID-19? (Yale Medicine)

For families and caregivers

- Helping Children Cope with Emergencies (CDC)

- How to Talk to Your Anxious Child About the Coronavirus (Psychology Today)

For physical distancing

- Preventing Loneliness in Times of Social Distancing (Psychology Today)

Ongoing lessons that can be learned from this experience

Beauty can emerge from experiences of turmoil; this is the premise behind a concept known as post-traumatic growth, which is defined as: “positive psychological change experienced as a result of adversity and other challenges in order to rise to a higher level of functioning.”

Perhaps it is a renewed wisdom about the importance of work-life balance and self-care, or a deepened level of empathy, humanity, and compassion for the hardships endured by our fellow human beings. Maybe it can be a recognition that we can confront the rigidity of “doing things a certain way,” and still be ok.

These concepts are not only applicable as “emergency medicine” in the face of a global health crisis, but can be thought of as our “daily multivitamin” as well. If we are able to speak about and start building some muscle memory for this now, hopefully it will serve us all well moving forward.

Enroll in the Master Class & earn 6 SHRM credits

Enroll in the Master Class & earn 6 SHRM credits